Breaking News 4: When real news is fake

For this article I’m defining fake news as “news stories that have no factual basis but are presented as facts” (taken from “Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election”), whether a site’s goal is to make money or make partisan political points.

Here are several ways real and fake news are the same. In both:

- Most people don’t trust the media.

- No one formally fact-checks the articles.

- The articles often have errors.

- Reported errors rarely get corrected.

- Bogus information surrounds the stories.

- Publishers are complicit in ad-tech fraud.

Real news often promotes, funds, looks like and reads like fake news. Too many readers can’t tell the difference.

The man who never looks into a newspaper is better informed than he who reads them; inasmuch as he who knows nothing is nearer to truth than he whose mind is filled with falsehoods and errors.

—Thomas Jefferson (2007)

Most people don’t trust the media

People once believed in the media. In Gallup surveys, “Americans’ trust and confidence hit its highest point in 1976, at 72 percent, in the wake of widely lauded examples of investigative journalism regarding Vietnam and the Watergate scandal.” But our faith in mainstream media “to report the news fully, accurately and fairly” has been plummeting for decades.

A December 2016 60 Minutes/Vanity Fair poll asked, “Which industry is the most unethical?” The top choice was Media (37 percent), beating out such paragons of virtue as Big Pharma (30 percent) and bankers (19 percent). Confidence in the media has sunk to near Congressional lows.

GenForward asked young adults in a December 2016 survey if they had “trust and confidence” in the mass media to report “the news fully, accurately and fairly.” They didn’t: 42 percent answered “Not very much” and 28 percent said “None at all.”

No one formally fact-checks the articles

After major errors surfaced in a Newsweek story, spokesman Andrew Kirk offered this defense: “We, like other news organizations today, rely on our writers to submit factually accurate material.”

“I guess they don’t do fact-checking,” wrote Paul Krugman. He was right. But he failed to mention that neither does his paper:

Writers at The Times are their own principal fact checkers and often their only ones.

—“Guidelines on Our Integrity,” The New York Times (1999)

Teri Hayt, executive director of the American Society of News Editors, emailed me this explanation: “As the industry contracted, those journalists working in the news libraries and copy desks were laid off. Those two groups — especially at smaller and mid-sized organizations — were a wealth of knowledge. Reporters would often ask them to double check a fact.”

Anecdotally, she says, “errors went up. Sometimes small ones: The accident was at West Speedway not East Speedway. And sometimes the errors were large requiring a Page One correction.”

Editors work on clarity and grammar. Few, though, have time to confirm each date, detail and event. “Reporters have always been responsible for the accuracy of their content, but now there is no safety net,” wrote Hayt.

Consider all those unchecked facts, published every day, every hour, slipping through the editorial cracks. Each published error chips away at journalism’s credibility.

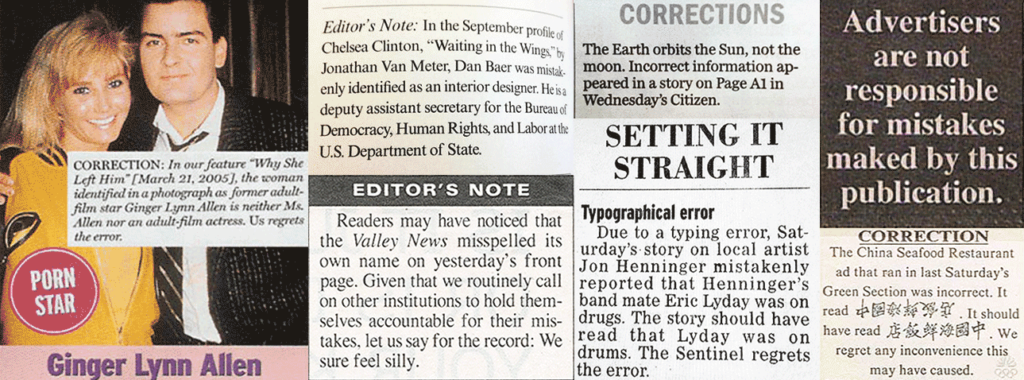

Articles often have errors and reported errors aren’t corrected

Why don’t Americans trust the media? Maybe because it’s not trustworthy.

More than 60 percent of local news and news feature stories in a cross-section of American daily newspapers were found in error by news sources, an inaccuracy rate among the highest reported in nearly 70 years of research, and empirical evidence corroborating the public’s impression that mistakes pervade the press. In about every other article, sources identified “hard” objective errors.

—Scott R. Maier, “Accuracy Matters: A Cross-Market Assessment of Newspaper Error and Credibility” (2005)

According to a 2016 Media Insight Project study, 85 percent of adults believe “accuracy is a critical reason they trust a news source.” But studies by Scott Maier of the University of Oregon (Go, Ducks!) show accuracy is not the media’s strong suit.

News errors rarely are corrected. In a study I did of factual errors reported to 10 daily newspapers, I found that nearly all — 97 percent — went uncorrected. Nevertheless, survey research indicates the majority of U.S. newspaper editors and reporters believe that a correction “always” follows a detected error. This level of faith is not widely shared by newspaper readers.

—Scott R. Maier, “Confessing Errors in a Digital Age” (2009)

Bogus information surrounds the stories

Too often news organizations play a major role in propagating hoaxes, false claims, questionable rumors, and dubious viral content, thereby polluting the digital information stream. Indeed some so-called viral content doesn’t become truly viral until news websites choose to highlight it.

—Craig Silverman, “Lies, Damn Lies, and Viral Content,” Tow Center for Digital Journalism (2015)

Writing about a fake news story can boost that story’s social shares, search engine rank and ad dollars. Linking does the same. (See First Draft News: “That debunk of a viral fake news story might help the hoaxers: Here’s how to stop it.”)

Next to most news stories are those sponsored links — news-like headlines “recommended” by robots — known as chumboxes. A 2016 study of vendor links by ChangeAdvertising.org reported “only 46 percent went to what appeared to be legitimate advertisers,” while 30 percent linked to clickbait and fake-news sites.

Then below the chumbox sits the steaming pile of partisan bickering labeled comments. For a dim view of humanity, read the flame wars under this first lady’s speech.

Why would readers believe a publication prints true, nonpartisan stories when false, inflammatory information (in the comments) and links to fraudulent and hyperpartisan sites (in the chumbox) follow each article?

Can you tell which of the following are real news sites and which are not?

Similar design and similar ads make it hard to spot the differences (answers below). One difference, though, is mainstream media sites use more ad tech. So on average they’re slower, less secure and more privacy invasive.

Publishers are complicit in ad-tech fraud

Fake news is now big business. Its business model depends on the fraud-infested ad-tech industry. Ad tech depends on legitimate news sites ignoring its often-illegitimate practices, which the World Federation of Advertisers predicts will become “second only to cocaine and opiate markets as a form of organized crime.”

News sites profit from and contribute to the most corrupt, least-effective advertising ever. Among the numerous online malignancies spawned is the thriving fake news business.

Fabricated and biased stories propagate faster and farther than real news, making lots of money along the way. Beneficiaries like Google and Facebook have often vowed to stop spreading fake news. But, historically, corporations haven’t excelled at cutting their own revenue sources.

Mainstream media must save itself

A good start to solving this problem would be to create websites that readers can immediately identify as reliable — visually and factually.

To fight fake news, don’t be like fake news. Stop promoting it. Stop funding it. Stop looking like it. Stop writing like it.

Answers: Which sites are real news and which are not? (Based on OpenSources list of “Not Credible” sources.)

- Top left, Time: real.

- Top right, Breitbart: unreliable, biased.

- Bottom left, San Francisco Chronicle: real.

- Bottom right, Now the End Begins: conspiracy.

Josef Verbanac of Montana State University contributed to this report.