https://readtheplaque.com/plaque/ida-b-wells

What does movement journalism mean for journalism as a whole?

“The goal is always going to be with the people”

The views expressed in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Reynolds Journalism Institute or the University of Missouri.

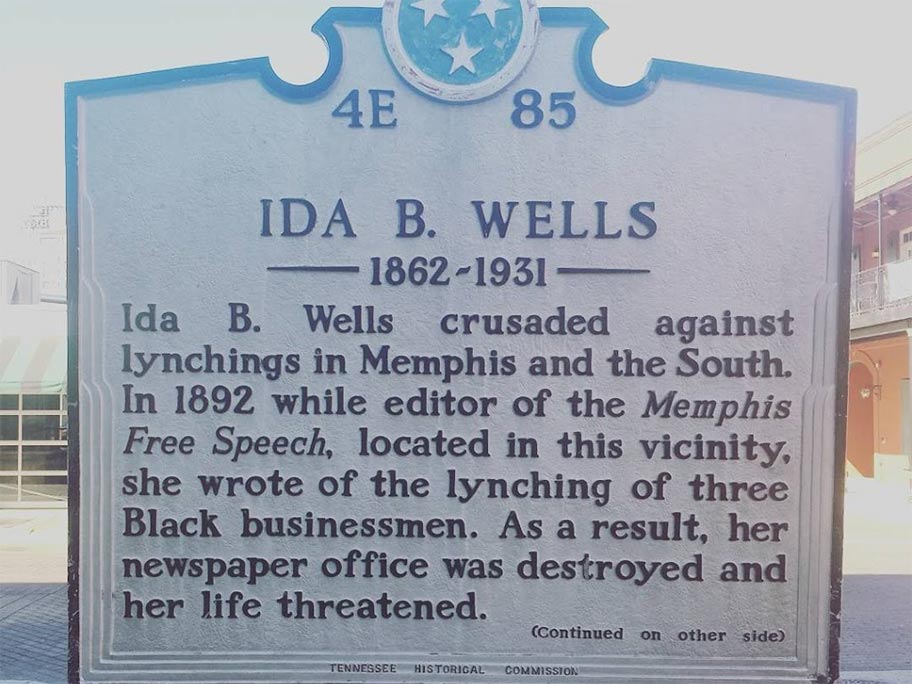

Movement journalism. It didn’t yet have the name, but still, it was there in practice when Ida B. Wells’ name was first placed on the masthead on the Memphis Free Speech in 1892.

Wells, a Black journalist who meticulously reported on lynchings across the American South, sought justice and truth when many journalists wouldn’t. Wells was derided in her own time by many newspapers for her direct challenge to white supremacist narratives parroted by those same outlets, and she has never truly been centered in the historically white-led mainstream American journalism tradition.

Her work, and the work of other journalists like Marvel Cooke and Claudia Jones, are the foundation that movement journalism is built on.

The term “movement journalism” was popularized in a 2017 report put together by Anna Simonton, a journalist and then-communications fellow at Project South, a movement-building organization in the South. Simonton writes that movement journalism is the practice of journalism in the service of “people coming together to build the power of all people to collectively control the conditions of our lives and our communities.”

For several journalists — many of them queer, Black and brown — elements of this tradition and framework, which centered in the South, permeated through their work long before it had a name. For others who are newer to the idea of unlearning status quo journalism practices, it’s the terminology — movement journalism — that gave them a new language.

Movement journalism represents a fissure in American journalism. It is a framework opposed to mainstream journalism practices — which still often prioritize the comfort of white male cisgender voices — in the guise of “objectivity.” And many of the journalists that practice it seem unconcerned with larger legacy newsrooms that are preoccupied with stature and tradition, instead of emphasizing the importance of doing right by the communities they report with.

“I think a lot more people would consider themselves movement journalists if they simply knew what it was,” said Ko Bragg, a reporter at The 19th. The 19th focuses its journalism at the intersection of gender, politics and policy. “I would say I was trying to do this journalism before I realized: ‘Oh, there’s a name for that…’ Kind of in direct opposition to the way journalism is traditionally and historically done.”

“The goal is always going to be with the people, so it totally bucks the metrics of what we even think of as success, ” said Bragg, who is also a contributing editor to Southerly, which covers the intersection of ecology, justice and culture in the American South.

“I went to journalism school — the way a lot of us are taught — you say you made it if you’ve worked at The Post, The Times. My family does not read The New York Times on a day-to-day basis. They don’t read these big newspapers; they read their local papers and often are frustrated with the fact their communities are left out of them.”

Cierra Hinton, the executive editor of Scalawag, said that she was looking for a way to define the work she wanted to do as a journalist. She found that framework in movement journalism. In that vein, Scalawag aims to use movement journalism frameworks to guide its reporting and publishing. To that end, the publication offers frank statements, calling white supremacist violence out for what it is and in-depth reporting that illustrates community power in opposition to hostile policy.

“There were a lot of instances where we were trying to put our finger on this thing that we wanted to do differently in journalism that we weren’t really seeing folks do currently,” Hinton said. “We don’t want to just be producing journalism for the sake of producing journalism. We’re not trying to replicate the things that we’ve seen.”

PressOn

Many of the journalists involved with movement journalism can be tied back to PressOn, a collective organization co-founded by people like Simonton, Manolia Charlotin, Mia Henry and Chelsea Fuller to advance justice through the practice of movement journalism. Bragg served as a mentor for PressOn’s Freedomways, a fellowship committed to justice-centered reporting that prioritizes women of color and LGBTQ+ people rooted in the American South. Hinton is the organization’s co-director of strategy and operations.

The organization may have the most concise definition of movement journalism: “Movement journalism is journalism in service to liberation. This does not mean turning journalists into soapboxes for activists, but fostering collaboration between journalists and grassroots movements, and supporting journalism created by oppressed and marginalized people.”

Outside of work directly with PressOn, several journalists have attempted to explain the state of movement journalism. Tina Vasquez, a board member at PressOn and initially a Freedomways mentor with Bragg, has extensively written about the framework.

Vasquez, a senior reporter for Prism, writes for NiemanReports that her understanding of movement journalism was inspired by Simmonton’s report, PressOn, and Lewis Raven Wallace, another co-founder of PressOn and author of “The View from Somewhere.”

Movement journalism represents a fissure in American journalism. It is a framework opposed to mainstream journalism practices — which still often prioritize the comfort of white male cisgender voices — in the guise of “objectivity.”

In that same piece,“Is Movement Journalism What’s Needed During this Reckoning over Race and Inequality?”, she explores the roots of movement journalism and her education about the framework. Vasquez illustrates her own practice of movement journalism principles, working collaboratively and aiming to reduce harm, by describing her reporting with undocumented immigrants that left sanctuary churches in North Carolina to organize and develop deportation defense campaigns.

“It required an enormous amount of trust on behalf of the people in sanctuary and the organizers working with them, and endless negotiations about what was safe to publish and when,” she writes.

Vasquez also asks a critical question: What does movement journalism mean for journalism as a whole? Can it exist inside the mainstream?

She concludes that, while she initially presumed journalists of color writing about communities of color would embrace movement journalism, that wasn’t the case considering “how hard journalists of color have to fight for their reporting to be seen as valid.”

Vasquez’s reporting supports that conclusion well. It’s a problematic bind: Reporters of color are often hired with lived experiences and told to keep them out of their reporting, while white reporters are never told the same thing.

But the increased visibility of reporters like Vasquez, Bragg and Hinton, and groups like PressOn, have pushed others to identify with the framework and break away from traditional legacy newspapers.

What you do

Adam Mahoney recently graduated from the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University and now reports on environmental justice at Grist. But when he worked at the Chicago Sun-Times, a prominent legacy newspaper, he had a clear takeaway.

“I hated it,” he said. “Fitting in with a mainstream legacy publication is not just for me. And I think in the next couple of years, we’ll see more people branching out to do the kind of reporting they want to do on their own, not tied to any kind of corporate entity.” Young journalists like Mahoney who weren’t directly involved with PressOn are still finding movement journalism and embracing it.

Mahoney is concerned about movement journalism being co-opted by larger institutions to the detriment of the work itself. As is Raven Wallace, who when we spoke said he worries about movement journalism becoming a “calcified identity.”

“It’s sort of like ‘ally’ or something like that,” he said. “Where it’s really about what you do and not about who you say you are.“ In part, that means producing journalism that aims to reduce harm and strives not to be extractive or exploitative.

Raven Wallace said this year and last, he’s seen and heard of news organizations claiming to do movement journalism without any accountability to movements led by oppressed people.

He believes it’s critical for organizations to acknowledge the historical legacy of movement journalism as one that comes from women of color, and in particular Black women, who have risked their lives to do this kind of journalism.

Raven Wallace, who got his start practicing movement journalism through trans community and anti-racism activism, said there is still a concern about his visibility as a white trans man, when movement journalism aims to center people of color, primarily the work of Black women in the south. “My book or my work is at the center of that conversation really runs the risk of making invisible all of the people of color who have been saying the same things and making the same points and not gotten that sort of credit or not have their names,” he said.

Journalists like Raven Wallace, Bragg, Vasquez, Hinton and Mahoney articulate their work as informed by movement journalism, but their voices are still a burgeoning force in the field. Those that practice the same principles may not identify with the term or have even heard of it. Yet.

Doing the work

The conversation in newsrooms, in many cases, isn’t ready for a frank discussion about which values and frameworks reporters can use because many newsrooms refuse to adopt any concrete values at all beyond vague notions of “objectivity” and “fairness.”

But reporters are doing the work. It’s not a generational divide, and while it is an inherently political one, it’s more clarifying to frame it as a moral divide: Either reporters are writing for themselves or their institutions, or writing for communities ignored and distorted by the mainstream press in the U.S.

“Movement journalism will not be like the dominant thing until it is the dominant thing. As the status quo shifts, I think we will start to see more and more people and outlets gravitate toward movement journalism as a practice that feels aligned to their values, and what they want to be true when they’re working in community,” Hinton said.

“If we ever dismantle the current system of power that we operate in — namely white supremacist, capitalist, patriarchy — then movement journalism, I think, could be what journalism looks like in a liberated future.”